Some time ago I published an article entitled What Is Depreciation in Real Estate. Today I’d like to further consider what impact depreciation has on taxation upon the sale of an asset – the capital gains, by shedding light on the concepts of Cost Basis, Taxable Income, and Capital Gains as they relate to a sale of investment property.

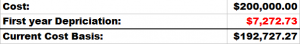

For the proposes of this article, I am going to continue with the example of a 6-plex that you bought for $200,00o. To keep things simple, we are using the entire $200,000 as the basis for figuring annual depreciable expense, though, as you know, the land is not depreciable therefore in reality we would not be able to depreciate the entire purchase price. But to keep things simple for the sake of our example, we simply divide $200,000 by 27.5 to arrive at $7,272.73 of depreciable expense per annum.

WHAT IS COST BASIS

On day 1 of ownership, Cost Basis is essentially what you pay for the property – the purchase price. However, as time goes on and every year you depreciate the appropriate amount every year, in our case $7,272.73, the cost basis diminishes by the same amount. Thus, after 1 year of ownership, the cost basis for the 6-plex that we’ve been talking about will be $192,727.27:

As you can see, all I’ve done to recalibrate the Cost Basis is subtracted one year’s worth of depreciable expense ($7,272.73) from the initial cost. Now – continuing with this train of thought, the Cost Basis after 10 years of ownership will be $127,272.73:

In order to see why this is important, we must now address the concept of Taxable Income.

TAXABLE INCOME

Piscataway homes for sale experts elaborate, “Here’s the thing; while the IRS was very nice to you during the life of the investment in allowing you to depreciate property which created a shelter for some of the income and thereby savings on your tax bill, when you do decide to sell – no more nice… The IRS wants their money – the money that they missed out on by allowing you to depreciate your property.

One of the ways they get you is by recapturing the depreciation that you took, which basically means that they tax the entire amount you depreciated over the time you’ve owned the asset. The proper term for this amount of money is Taxable Income.

Think of it this way; taxable income is the income that you should have been taxed on all along but weren’t due to being able to shelter it with the depreciation deduction. Now you will PAY!

For Example

Let’s say that you decide to sell this 6-plex after 10 years, and in that time it had appreciated to $230,000. In this case, the total amount of depreciation that you will have claimed will be $72,727.27. Thus, your Cost Basis left in the deal will be $127, 272.73:

Your Taxable Income in this case, provided you sell the property for at least as much as what you paid for it, will be $72,727.27. If you sell it for less then the IRS can not recover all of the deducted depreciation. The amount of tax that you will pay on this amount will be consistent with you income tax bracket in the year when the sale takes place. The proper formula for taxable income is:

Taxable Income = Cost – Current Cost Basis

(but the answer is basically the sum of all depreciation that you’ve taken over the years)

However, if you do sell the property for $230,000 having bought it for $200,000, this is not all that you will be taxed on…

CAPITAL GAINS

Since you were able to sell the asset for more than what you paid for it, the amount by which the sale price exceeds what you paid (Cost) becomes your Capital Gains, which is currently taxed at 15%, but may be going up soon. So, having paid for the property $200,000 and sold it for $230,000, your Capital Gains will be $30,000.

Thus, in this example you will be taxed on a total of $102,727.27, but a different rate will be applied to $72,727.27 taxable income and $30,000 of capital gains.

HOW MUCH CAPITAL GAINS TAX DO I HAVE TO PAY

Capital Gains tax comes in two basic varieties: long term and short term. The short term capital gains is assessed at whatever earned income tax bracket you fall into, and is potentially applicable to transactions that are shorter time-frame than 12 months. In our case, however, we would be dealing with long term capital gains, the current level for which is 15% for most tax payers. Therefore, having sold the asset for $30,000 more than what you paid for it, your capital gains tax exposure would be $4,500:

$30,000 x 15% = $4,500

WHAT IS THE OVER-ALL TAX EXPOSURE

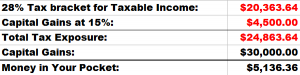

And since we are talking about tax exposure, let’s cover the big picture as well. Assuming a 28% tax bracket and a 15% Capital Gains Tax rate:

As you can see, at an income tax rate of 28% and a CAP Gains rate of 15%, your total exposure on this sale is $24,863.64. This means that having generated a profit of $30,000 on the sale (i.e. having sold the asset for $30,000 more than what you paid for it), you will only put $5,136.36 in your pocket. It is evident that the recapture of depreciation causes the majority of the damage here. What’s worse is that if the Long Term Capital Gains tax goes up to 20% from the current 15% for most tax payers, which is likely and would be historically acceptable, then all you would take home after taxes would be $3,636.36!

Thus, while depreciation certainly helps us during the time of ownership, the tax bill does catch up to us. The only legal way to avoid paying taxes upon the sale of property is a Tax-Deferred Exchange, which allows us to defer (postpone) payment of taxes so long as the proceeds are invested in a bigger like-kind investment. This works, though has its’ own difficulties and limitations, but this is outside of the scope of today’s article.

The mitigating factors here are the notion Passive Cash Flow throughout the life of the investment, which is taxed at the lowest possible Capital Gains rate, and our ability to force appreciation. Both create opportunities to increase the spreads over the life of the investment considerably…more on this in up-coming posts.

Hope this further clears some things up for you guys as far as depreciation and all things taxation. Questions? Comments?

Photo Credit: EricGjerde via Compfight cc

10 Comments